My papa and his brother would plough all day and come in and play music every night. My papa used to take his fiddle out after supper. I can see him now.2

Moi, j'connais, moi j'ai vu, dans le brouillard, hier matin,J'ai demandé à ton papa pourquoi tu viens pas à la maison.Ton papa et ta maman z'é (?)m'as dit, malheureuse,C'est trop jeune pour tu t'aimé avec ton neg', oh, yé yaille,Quelles nouvelles que moi j'attends, chère 'tite fille, ça crève mon cœur,Mais comment donc moi j'vas faire, moi tout seul, malheureuse.C'est la danse que j’étais z'avec toi, mais malheureuse.Mais (re)garde encore qui sont aprés faire avec nous autre aujourd'hui.Ecoute pas ton papa (et) de ta maman, oh, chere 'tite fille.Et tu vas venir dans la maison z'avec moi d'un jour à venir.

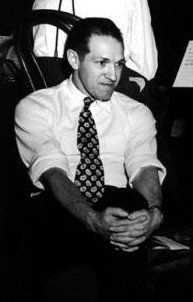

|

| Moise Robin |

Cajun musician Moise Robin was the second accordionist that Leo chose to work with. The two began performing together in 1928, shortly after Soileau’s first partner, Mayeus LaFleur, was shot and killed. During the summer and fall of 1929, they recorded for three different companies: Paramount, Victor, and Vocalion. Together, they traveled to the Gennett Recording Studio, Starr Piano Company Building, Whitewater Gorge Park in Richmond, Indiana around July of 1929. The session produced "Je T'ai Recontre Dans Le Brouillard" (#12908). The accordion melody could have been inspired by John Bertrand's "Rabbit Stole The Pumpkin", however, the vocals are unique on their own. Misspelled as "Je Te Recontrai de la Broulier", Moise sings of young girl chasing an older man, a song most likely self-composed. Moise recalled,

I made the songs myself, when I was young. My dances and my tunes and my songs, I would write in French and understand my own language, you see. So I would compose my songs and write them down and practice them.4

I know, I saw through the fog, yesterday morning,I asked your dad why you didn't come home.Your dad and your mom told me they're unhappy,That's too young for you to be in love with an older man, oh yé yaille,That news I awaited for, dear little girl, burst my heart,Well, how am I going to make it all by myself, oh my.This is the dance I had with you, well oh my,Well, look who's still with us after another day,Don't listen to your dad and your mom, oh dear little girl,And come to the house with me another day in the future.

When the recording session was done, the engineers began producing the recordings on 78 RPM records. Unfortunately, when it was time to press the previous song "La Valse De La Rue Canal", Paramount engineers mistakenly replaced it with audio of "Je Te Recontrai De La Broulier". Today, the original Soileau and Robin recording of "La Valse De La Rue Canal" has yet to surface.

- The Ville Platte Gazette (Ville Platte, Louisiana) 06 Feb 1969

- Times Picayune. Leo Soileau. 1975.

- Image courtesy of the Arhoolie Foundation

- https://arhoolie.org/moise-robin/

15345-A Ce Pas La Pienne Tu Pleur | Paramount 12908-A