In the 1920s, some of the most talented accordion players to rise among the ranks of Cajun musicians were born and raised along the Bayou Teche. Artists such as the Segura Brothers, Didier Hebert, Columbus “Boy” Fruge, the Guidry Brothers, Artelus Mistric, Berthmost Montet and Joswell Dupuis were some of the lucky few to score recording contracts with major recording labels. But none of them had become as infamous and garnered such wild notoriety in later years as Arnaudville-native Moise Robin. His life and early success was followed by self-inflicted tragedy and regret that affected not only his family, but the whole community.

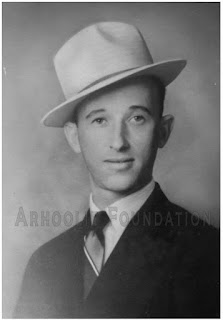

Joseph Moise Robin was born January 4th, 1911 in Point Claire, a small community between Leonville, Louisiana and Arnaudville, Louisiana. His father, Joseph, was a talented accordion player in his own right. “He played all over, around the territory Ville Platte and everywhere, play dances, for many years”, Robin told Chris Stratchwitz in 1980. “My daddy was born in 1886 … And he started play when he was young.” Moise began borrowing his father’s accordion and by the age of nine, he was assisting him at dances. “He would make me play a few dances for the people that took those great, big, red accordions, old time, and just my head would show up on top of the accordion.” Moise struggled to keep up and his vocals could never attain the sound that he desired. “I didn't have a good voice,” recalled Robin. “It was too low and I never had a good voice up to this day. One of my friends advised me to drink raw eggs and that would cause me to have a beautiful voice. So, I started watching the chicken house and looking for eggs.”

Joseph Moise Robin was born January 4th, 1911 in Point Claire, a small community between Leonville, Louisiana and Arnaudville, Louisiana. His father, Joseph, was a talented accordion player in his own right. “He played all over, around the territory Ville Platte and everywhere, play dances, for many years”, Robin told Chris Stratchwitz in 1980. “My daddy was born in 1886 … And he started play when he was young.” Moise began borrowing his father’s accordion and by the age of nine, he was assisting him at dances. “He would make me play a few dances for the people that took those great, big, red accordions, old time, and just my head would show up on top of the accordion.” Moise struggled to keep up and his vocals could never attain the sound that he desired. “I didn't have a good voice,” recalled Robin. “It was too low and I never had a good voice up to this day. One of my friends advised me to drink raw eggs and that would cause me to have a beautiful voice. So, I started watching the chicken house and looking for eggs.”THE RISE

By his late teens, Robin had a chance to make it big. In 1929, Ville Platte fiddler Leo Soileau lost his accordion playing partner Mayuse Lafleur in a brawl outside a bar room. By the time Leo was ready to resume his professional career, he contacted Moise. “He heard about me”, said Robin. “So he came home with my daddy and seen me that’s when he got me to play with him. So, I replaced [Lafleur]. And the first place we went, we played all around in clubs.” Paramount Records heard that scouts for RCA and Columbia were scoring big regional hits with Cajun musicians and their executives wanted a piece of the action. By July, they were in contractual discussions with Opelousas sewing machine seller and record dealer, Winter Lemoine.

Lemoine was a native of Leonville and a distributor for Paramount records in the region. Along with Leo’s history of recording, Lemoine arranged the duo to travel to the Starr Piano Company Building in Whitewater Gorge Park in Richmond, Indiana where the Gennett Recording company had constructed a studio. “So we met in Richmond, Indiana and made two records there,” recalled Robin. “It was all steam trains …They would pay all expenses, and the year was, in that time, money, it was Depression, $25 each, to make that first record. And it was great for us to $25.”

The duo recorded six sides for the label and the future was looking good for the young Robin. Soon after, RCA contacted Leo in September for another session, however, this time, Robin tagged along. “We was called to Memphis, Tennessee, me and Leo, and made again two records there.” RCA record scout Ralph Peer was in charge and had previously worked with Opelousas merchant and agent for Leo named Frank Deitlein. Frank had paid for the duo’s travel and brought along Columbus “Boy” Fruge. “In the grand ballroom in the Claridge Hotel, where the Victor company did their recording, the four of us entered and were greeted by a fellow by the name of Ralph Peer,” recalled Frank. “I believe that he was president of the Southern Music Publishing Co., which specialized in recording Southern folk songs.” Leo and Moise recorded four songs followed by Columbus who recorded another four tunes.

Moise’s career had reached a pinnacle point. However, dark times loomed ahead. He and Leo’s professional relationship was starting to sour, and their personalities were showing signs of conflict. Both men seemed to disagree on each other’s technique and the New Orleans session would be Robin’s last. When folklorist Ralph Rinzler asked Robin why they split, he explained their performances were suffering. “It's the same D, G, C,” exclaimed Robin. “There's no chorus in that son of a gun (Cajun music)... accordion and fiddle, it's just you got to pap. You just can't stop.” Their split wasn’t the only reason the recording opportunities ceased. The end of 1929 signaled the Great Depression and all southern scouts declined to record Cajun music for another five years.

Throughout the mid-1930s, Leo would continue recording and playing in regional dancehalls throughout the southwestern part of the state, recording for other labels such as Bluebird and Decca, while Robin found himself content playing music in small bars around Arnaudville. These bars rarely were places hosting grand cosmopolitan events. They catered to rural folks, generally farmers, that were looking for an escape from the daily grind. With the economic effects still lingering from the Depression, alcohol consumption increased, and with it, the pension for violence in bars did too. On July 24th, 1937, while playing late night at Forest Dupuis’ Dance Hall outside of Leonville, five men approached Robin and attacked him with knives. When officers arrived, Robin was found slashed across his abdomen and he remained in critical condition at his home. All five assailants were arrested however, Robin’s problems were only beginning.

THE FALL

Moise’s rough and tumble livelihood spilled out into his relationship with his wife Louise. The couple married in 1934 at the Leonville church and had a daughter Erilda soon afterwards. But their relationship was never stable. In 1949, everything came crashing down. Late at night on September 12th, 1949, Louise and Moise had gotten into another dispute. They had been quarrelling over a week, however, this time, Louise wasn’t interested in arguing anymore. She made it clear that she was leaving him. To top it off, she threatened to take custody of both of their daughters. Angry, Moise threatened her life if she ever left him but she had already made up her mind. Louise packed her things, grabbed their two daughters, fled their house in Leonville and headed to her father Ovide Richard’s house in Paccaniere.

In a fit of rage, Moise jumped into his car and headed to her father Ovide’s home. Not to alarm the family of his presence, he parked his car a considerable distance from the Richard home, walked through the fields and entered the home from the back door. Quietly, he walked into the house, hoping to not alarm the other family members.

Louise, who was busy talking to her father, noticed Robin enter the adjacent room. Immediately, she screamed and ran toward her father. Suddenly, Robin revealed a 12-gauge sawed-off shotgun, loaded with buckshot. He fired directly at her face and after she fell to the ground, he vengefully fired a second shot into her back. According to Robin's daughter Erilda, “I did not see [Moise] come in but I saw him when he was at the door and when he shot. Then I ran to the bathroom and then into the front room where my mother was.” Louise’s mother lay on the ground, cradling her daughter’s head.

Several pellets from the shot missed his intended target and lodged in Ovide’s foot. Knowing that Moise had used all the shells in his gun, Ovide tried to prevent Moise’s escape. Ovide explained during the hearing, “I jumped over my daughter and ran in the back room, the same room that Moise had shot from. I grabbed my shot gun and went after him but he had gone out in the dark and I did not see him after that.”

Robin fled the scene. He arrived at his sister Alfreda’s house where he explained to her that he killed his wife and was going to kill himself. Robin's nephew, after hearing the news, jumped in a car, attempting to chase him. Robin left Alfreda's home and ended up finding a pistol at his father's house. Before anyone could stop him, Robin fired a round into his own head and another one that entered the left side of his face. Amazingly, Robin survived. He was taken to the Arnaudville sanitarium, surrounded by security guards.

The shock from the event rippled across Cajun communities. Newspapers across the state were suddenly covering the case and all the gruesome details. The coroner labeled her death from “shock and hemorrhage from a gunshot would into the abdomen and liver inflicted by Moise Robin.” He stayed in an Opelousas hospital until he could recover enough to be moved to the St. Landry parish jail at Opelousas. Later that month, a grand jury was formed where they indicted him on murder charges for the slaying of his wife. They transported him to Angola State Penitentiary where he awaited the results of the investigations.

In October, he began another attempt to kill himself. For nine days, he went on a starvation diet. He eventually regained his awareness after being admitted to the prison hospital where they injected fluids and nourishment. Superintendent Lawrence believed he had “somewhat improved but remained in pretty bad shape.” In November, a panel of specialists were assigned to judge Robin’s mental condition in order to determine if he was fit to stand trial. Although Angola physicians believed he was improving physically, they claimed “he is so mentally confused and incompetent that he is unable to care for himself, has to be fed, bathed, and have his bodily needs attended to”. They also claimed, in the presence of witnesses and a Catholic priest, Robin said he had “just seen the Blessed Virgin and spoken to her” and that “he would perform miracles” before he died. His attorneys contended that such delusions and irrational statements question Robin’s sanity.

By December, the judgement arrived from Judge Lessley Gardiner. Moise Robin was declared “insane, incapable of understanding proceedings against him or of entering into his own defense” by Dr. Magruder and Dr. Robards. Robin was transferred from Angola to the East Louisiana State Hospital’s criminal insane department in Jackson in early January of 1950.

He remained at the sanitarium as a mental patient for 17 years until October of 1966. He decided to plead guilty to the charge of manslaughter in order to receive a five-year suspended sentence. The medical staff notified the district attorney that Robin was “capable of taking part in his own defense”. He was returned to the St. Landry Parish jail where he awaited his fate. Judge Gardiner placed Robin on five-year active supervised probation by a psychiatrist.

THE REDEMPTION

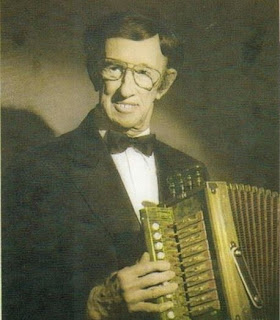

By 1968, Robin believed he was a changed man. Like many ex-convicts, Robin was convinced that he was in the midst of a "religious awakening". The time he spent in confinement would be used to redeem himself and move into a more familiar lifestyle. He met Marie Artigue, a companion that he remained with, although they never married. Robin even considered performing music again. He formed a small group called the Opelousas Playboys, playing at small venues such as Richard’s Casino in Lewisburg. Both record producers, J.D. Miller and Eddie Shuler, took chances and recorded Robin in their respective studios, releasing several singles on 45 RPM records.

By 1983, the guilt of his offenses began to weigh on him and he spent time writing religious laments claiming, “he was led by a spirit" to write a book by the name of ‘The Golden Gate’. In it, he attempts to redeem himself in the eyes of the public and loosely writes about premonitions and future predictions, all with a spiritual flare. He took out ads in the paper to sell his book, making exorbitant claims, hoping his public perception about him would change.

In the end, he would freely admit his falling from grace. He told others in documentaries, such as Gerard Dole, Chris Strachwitz and Marc Savoy, of the things that had happened, although, after much time had passed, details were missing from his recollection. He performed for the 1984 Festival Acadian with his Arnaudville Playboys and continued selling his book in small shops. He often teamed up with Doc Guidry and Faren Serrette, playing at places such as Pat’s Waterfront Restaurant, Eunice’s Liberty Theater and area festivals. Gerard Dole recorded Robin playing one last time in 1989 for his CD release of “Le Légendaire Moise Robin”. It seems Robin never used his music to hide from his time during incarceration and thought others should take note of his spiritual prophecies. According to Robin,

“And why should we believe a prisoner? Let me remind you that the 'Old Man' has always and always will choose a prisoner to do his spiritual work.”

- https://arhoolie.org/moise-robin/

- Clarion-News (Opelousas, Louisiana) 15 Sep 1949

- Clarion-News (Opelousas, Louisiana) 22 Sep 1949

- Clarion-News (Opelousas, Louisiana) 24 Nov 1949

- Daily World (Opelousas, Louisiana) 20 Dec 1949

- Daily World (Opelousas, Louisiana) 16 Oct 1966

- The Daily Advertiser (Lafayette, Louisiana) 06 Nov 1983

- Daily World (Opelousas, Louisiana) 26 Feb 1984